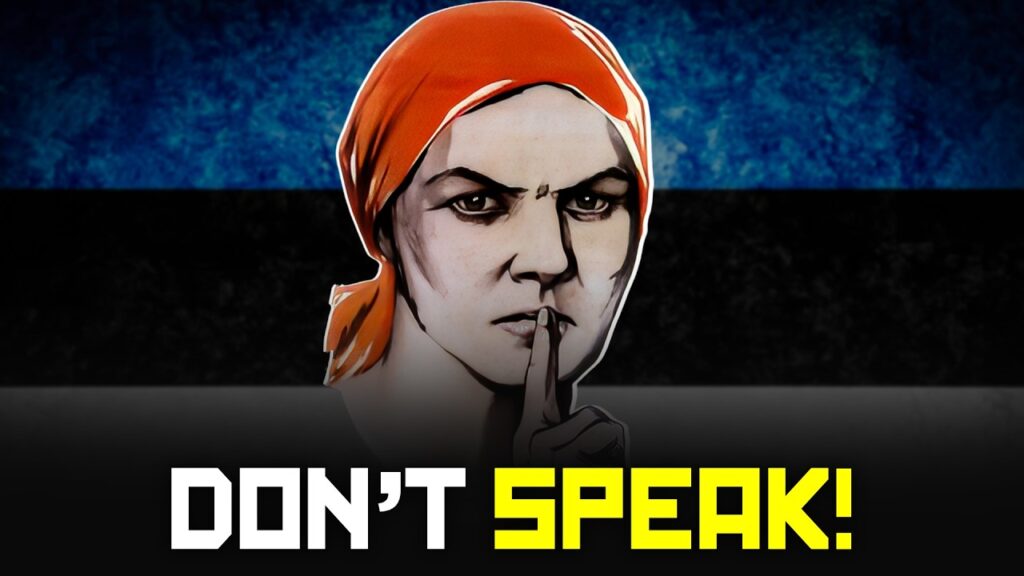

The Sad Truth About Life in Estonia Nobody Talks About

Estonia likes to present itself as modern, digital, Nordic, and forward-thinking—and in many ways, that image is deserved. E-government works. Institutions function. Daily life in Estonia feels orderly, predictable, and efficient.

But there is one uncomfortable area where the reality doesn’t match the branding.

And that gap matters far more than people realise.

It’s how the state deals with hate speech—and how uneven enforcement quietly shapes everyday life.

This isn’t a story about ideology. It’s about consistency, law, and what it actually feels like to live here when protection depends on who the speech targets.

Estonia’s Hate Speech Law: Legal on Paper, Weak in Practice

Under Estonian law, public incitement to hatred is only criminal if it directly results in danger to life, health, or property. That single condition changes everything.

In practice, it means:

Speech can be openly racist, xenophobic, or demeaning

As long as no immediate physical harm occurs, it’s usually not punishable

What many European countries treat as hate speech, Estonia treats as free expression.

This legal threshold places Estonia among the weakest hate-speech regimes in the EU. Brussels has flagged this repeatedly. Infringement proceedings were opened in 2020 and again in 2024, stating that Estonia had partially and incorrectly applied EU standards.

A reform bill was drafted in 2022—but political deadlock stalled it. One camp argued only race, nationality, and religion should be protected. Another argued protection should include LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, and other vulnerable groups.

The result?

No comprehensive hate-crime law. No clarity. No consistent deterrent.

When Enforcement Depends on Who You Are

On paper, the law looks neutral. In reality, enforcement often feels arbitrary.

In 2023, during a protest in Tallinn, demonstrators were detained and fined for chanting a pro-Palestinian slogan. Police classified it as hate speech. Later, the Supreme Court overturned the fine, ruling that an average Estonian would not automatically interpret the phrase as incitement to violence.

But the damage was already done.

The message was clear: certain expressions can bring immediate police attention—even if they’re later ruled lawful.

Contrast this with another public event: a torch-lit march involving far-right symbolism, including neo-Nazi imagery. No arrests. No crackdown. No visible enforcement.

The legal logic doesn’t change. The application does.

And once people notice that difference, trust erodes.

What This Means for Everyday Life in Estonia

You don’t need to attend protests to feel the effects.

Racism and xenophobia exist everywhere. What usually limits them is deterrence—the knowledge that there are consequences.

In Estonia, that deterrent is weak.

As a result, many migrants report:

Verbal harassment in public spaces

Racial slurs without repercussions

Being told to “go back where you came from”

This isn’t usually violent. It’s persistent. And that’s what makes it exhausting.

When the law doesn’t clearly draw a line, people learn what they can get away with. Passive racism thrives not because it’s encouraged—but because it’s rarely punished.

Why This Becomes a Mental Health Issue

For many foreigners, life in Estonia is safe in the physical sense. Streets are calm. Crime is low.

But safety isn’t just physical.

Living without legal reassurance—knowing harassment is unlikely to trigger consequences—creates constant low-level stress. Not fear, exactly. Something quieter. Something heavier.

You start calculating:

Is it worth reporting?

Will it go anywhere?

Will I be taken seriously?

Over time, that calculation becomes silence. And silence normalises the problem.

A Question Estonia Still Has to Answer

This isn’t about banning opinions.

It’s about whether laws are applied equally.

A democracy doesn’t just protect speech it agrees with. It protects people consistently—especially when speech turns into targeted hostility.

So the unresolved question for Estonia is simple, but uncomfortable:

Does the state want to fight hate speech as a principle

—or only suppress the speech it finds politically inconvenient?

Until that question is answered clearly, this contradiction will remain part of life in Estonia—quiet, persistent, and rarely acknowledged.

And that silence is the real problem.